-

Halide – why you must know it and why others will keep ignoring it

In this article, we are going to take an in-depth look at the Halide language, focusing on where it is on the language spectrum, and when you would use it.

Note: The source code for this article can be found at https://github.com/klosworks/halide_articles. You can also use this code as a starting point for your Halide projects.

Halide, created by some PhDs at Google in the mid 2010s, is one of the most impressive programming languages in the world. And it doesn’t even have its independent syntax. Embedded entirely in C++, as a so-called DSL (domain-specific language), it’s a solution for solving complex speed optimization problems in a convenient and declarative way. What normally takes a 1000 lines of tuned C++, including with obscure extensions like intrinsics, takes only 50 lines of Halide code. Where’s the catch, you might ask? Keep reading to find out.

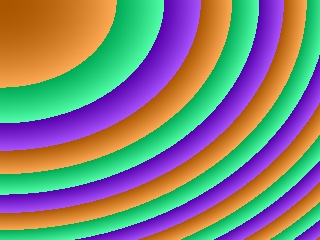

#include <Halide.h> #include <opencv2/opencv.hpp> int main() { using namespace Halide; Func gradient; Var x, y, c; Expr x_sq = cast<float>(x) * x, y_sq = cast<float>(y) * y; float a_sq = 200.f * 200.f, b_sq = 150.f * 150.f; gradient(c, x, y) = cast<uint8_t>(cast<int32_t>( (x_sq / a_sq + y_sq / b_sq) * 255.f + c * 85.f) & 0xff); Halide::Buffer<> output = gradient.realize({3, 320, 240}); cv::Mat_<cv::Vec3b> wrapper(240, 320, (cv::Vec3b*)output.get()->data()); cv::imwrite("gradient.jpg", wrapper); }

Example: a gradient image generated using Halide syntax.

1. Why is it the most awesome language I’ve seen?

In short, it solves a problem that, as I, an image processing programmer, had painfully found out, no-one had solved before. The problem is to give something better than C++ for writing image processing code. Not for training models that consist of neural networks, but for writing the code that needs to be written by hand.

The challenge of transforming images

Now, if you are thinking „who even has this problem”, let me clarify. If you know what the image processing field is about, you can skip this paragraph. There are different vision problems to solve with computers. They are of different nature. When we think about vision, what normally comes to mind is the classical under-definedness, where a camera has captured a complex 3D scene, we only get a 2D image, and we are supposed to somehow partially undo the 3D-to-2D transformation to find, for example, a human figure. This normally requires deep learning to take care of all the possible pose variations, light variations and occlusions that can occur. Some problems are more well defined, though. Some are simpler, such as working with scanned documents that are already in 2D to begin with. Some are about cameras mounted in constant locations such as CCTV, which allows comparing the pictures and seeing what has changed almost by the means of subtraction. Some are even observing objects that all have the same size and look the same, such as in a factory, above a conveyor belt that carries ceramic tiles. It is relatively easy to create a system, without using neural networks, that identifies defective tiles and signals an actuator to push them out of the belt. But some problems don’t even occur at the level of objects on the image. In denoising, for example, we don’t really care what’s on the image. We receive an image, a content distribution, such as „pictures taken by people with phones”, noise model like „if a pixel has value that is greater by more than 50 than all neighbors, it probably has incorrect value”, and all we need to do is to identify and smooth out those bright spots with low probability of destroying the actual image content. We could do this optimally in 50 lines of pure C++, if we so chose. There is no intelligence (beyond our own) or training required.

More generally, there are various applications of image processing that are optimized enough with normal code that they often don’t need deep learning:

- Industrial applications (monitoring, quality control)

- Medical imaging

- Consumer-level imaging (phone cameras etc.)

- Image editing

- 3D to 2D applications, such as structure from motion

- Graphical effects in video and games

Often image processing problems remain simple or aren’t resource constrained – the system only runs once in a while, such as on a slow assembly line, or is not latency sensitive, such as an image transformation in Photoshop. In those cases, one may be better off using an existing library, such as OpenCV and even using a slow language, such as python, to glue things together. (Although obviously Photoshop is run often enough by enough consumers that it makes total sense for Adobe to fully optimize the algorithms for speed.) But sometimes, such as when we want to do some quick image denoising on a user’s phone, time and power consumption is of the essence.

Some existing applications of Halide

In fact there is a whole suite of algorithms that we want to run on a picture when we capture it with a phone, from demosaicing, various kinds of denoising, up to tone mapping and intelligent dynamic range compression, for avoiding over- and underexposure. Some of those pipelines fall under the umbrella term HDR (high dynamic range). Wikipedia contains information about some types of such pipelines on the Multi-exposure HDR capture page. Halide is known to be the language of choice for at least one HDR pipeline, Google’s HDR+ as described in their publication (Hasinoff et al., 2016). They have gone even further in their use of Halide and they’ve created Pixel Visual Core – a dedicated chip to run image processing programmed in Halide (Shacham & Reynders, 2017).

Example non-HDR photo (left) and a HDR one (right). Note how on the HDR photo buildings are well-lit, instead of being too dark. Source: my own work, using the in-built HDR on a Huawei Mate 20 phone.

What it’s like to write the code and why we need a separate language

Computationally, these pipelines are wide and deep at the same time, meaning that each stage has data parallelism across pixels (wide), and at the same time there are a lot of stages (deep), just like in a deep neural network. They also have, what the Halide paper (Ragan-Kelley et al., 2013) calls „low arithmetic intensity”, which means a low cost of computation, as compared with memory accesses. It’s inherently impossible to write the fastest code possible for those kinds of pipelines using existing implementations, such as OpenCV algorithms. The problem is that the input-output of those library functions is an image buffer.

void cv::blur(InputArray src, OutputArray dst, Size ksize, Point anchor = Point(-1,-1), int borderType = BORDER_DEFAULT);Example of a typical interface of an algorithm in OpenCV. Source: OpenCV documentation

This means that if you have 6 OpenCV calls to make, you have to write to an image 5 extra times, to create intermediate results. Let’s examine why this is slow.

- The code is memory-bound. The alternative is combining arithmetic operations inside a single loop over the image, keeping intermediate results in local variables, for example doing an addition and a multiplication inside a single `for` loop instead of 2 separate loops. This saves us the cost of the memory reads and writes, but not only that.

- There is the notion of locality of reference, realized, among other things, by means of compiler optimizations and instruction pipelining, which means we can probably cram a lot of arithmetic operations per memory write without a lot of slowdown. We can take more advantage of this if we combine more operations (arithmetic and memory) in a single loop rather than working with a single array at a time. But this is not all still.

- The image processing does a ton of stencil operations. This means that, for example, that we loop over the whole image, and for each of the Width*Height pixel locations, we read a square local neighborhood of size 7×7 of values for the input array. A naive implementation will increase the number of reads 49 times! In practice, this further exacerbates the cost of accessing memory, sometimes by orders of magnitude.

- Also, having intermediate images means that we are much more likely to run out of cache with unpredictable loads from other programs. Remember that we are probably parallelizing our program, so we already try to maximize the use of cache on our side.

- Due to dependence of some results on eachother, we may have to keep many of the intermediate images in memory at the same time, drastically increasing the peak memory of our program. Note, a 4k x 3k RGB floating-point image takes over 137 MB! Only compressed images take little space.

So having these extra writes in between OpenCV calls can be really costly. To make this more concrete, let’s look at a specific example.

Example

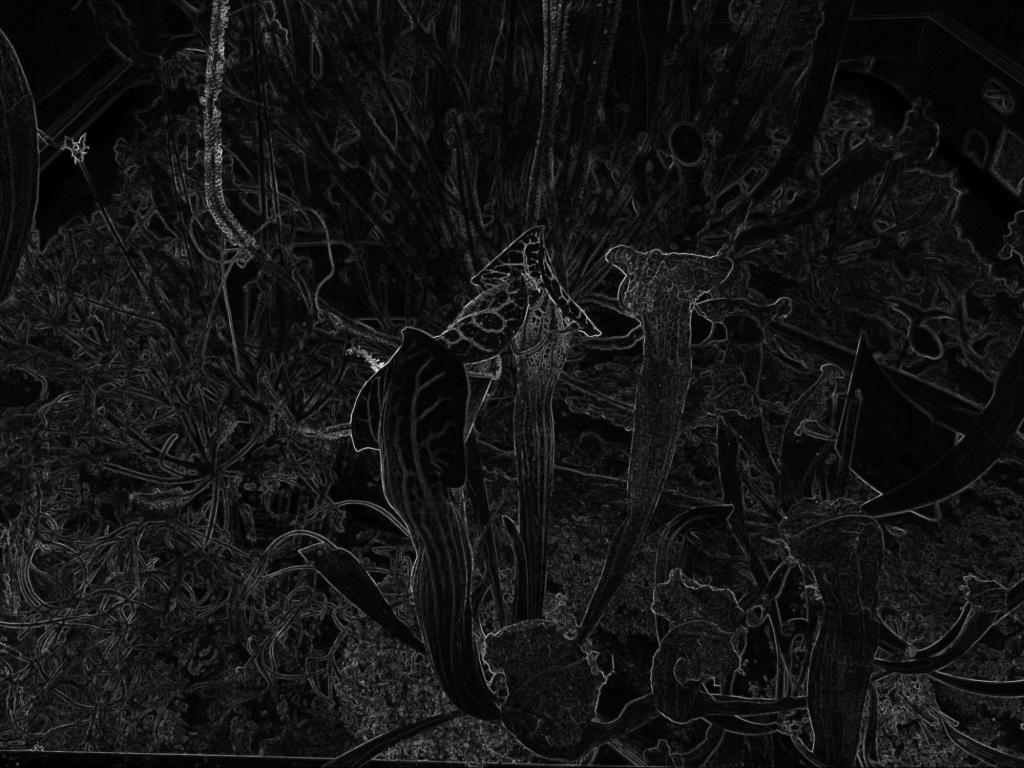

This program computes the spread in each 5×5 local neighborhood of an image. The spread is defined as the difference between the maximum and the minimum in the neighborhood. One way to write this in OpenCV is in terms of dilation, erosion, and a subtraction.

cv::Mat computeSpread(const cv::Mat& input) { using namespace cv; Mat dilated, eroded; //every pixel of dilated will have //the maximum of its 5x5 neighbors dilate(input, dilated, getStructuringElement(MORPH_RECT, Size(5, 5))); //every pixel of eroded will have //the minimum of its 5x5 neighbors erode(input, eroded, getStructuringElement(MORPH_RECT, Size(5, 5))); return abs(eroded - dilated); }The time this takes on my laptop is about 20.8 milliseconds.

As we can see, this tends to find edges, as well as light up in some areas where there is a high contrast at the scale of 5×5 neighborhoods.

If we were to optimize this, moving all the computations inside the individual loops, doing parallelization and vectorization, the code grows and gets out of hand. It may look like the following (adapted from halide tutorial 9).

Please, note:

- You don’t need to read the following code, I merely wanted to show that it’s long

- There may still be some optimizations available, like better vector instructions, but it doesn’t matter. The main purpose of this code is to show what such optimized code looks like, with tiling, vectorization, a circular buffer and so on.

cv::Mat computeSpreadCppVersion(const cv::Mat& input) { cv::Size size = input.size(); cv::Mat c_result(size.height, size.width, CV_8UC1); #ifndef __SSE2__ #error "you must have SSE2 for this code to work" #endif #pragma omp parallel for for (int yo = 0; yo < (size.height + 31) / 32; yo++) { int y_base = std::min(yo * 32, size.height - 32); // Compute clamped in a circular buffer of size 8 // (smallest power of two greater than 5). Each thread // needs its own allocation, so it must occur here. int clamped_width = size.width + 4; uint8_t *clamped_storage = (uint8_t *)malloc(clamped_width * 8); for (int yi = 0; yi < 32; yi++) { int y = y_base + yi; uint8_t *output_row = c_result.ptr<uchar>(y); // Compute clamped for this scanline, skipping rows // already computed within this slice. int min_y_clamped = (yi == 0) ? (y - 2) : (y + 2); int max_y_clamped = (y + 2); for (int cy = min_y_clamped; cy <= max_y_clamped; cy++) { // Figure out which row of the circular buffer // we're filling in using bitmasking: uint8_t *clamped_row = clamped_storage + (cy & 7) * clamped_width; // Figure out which row of the input we're reading // from by clamping the y coordinate: int clamped_y = std::min(std::max(cy, 0), size.height - 1); const uint8_t *input_row = input.ptr<const uint8_t>(clamped_y); // Fill it in with the padding. for (int x = -2; x < size.width + 2; x++) { int clamped_x = std::min(std::max(x, 0), size.width - 1); *clamped_row++ = input_row[clamped_x]; } } // Now iterate over vectors of x for the pure step of the output. for (int x_vec = 0; x_vec < (size.width + 15) / 16; x_vec++) { int x_base = std::min(x_vec * 16, size.width - 16); // Allocate storage for the minimum and maximum // helpers. One vector is enough. __m128i minimum_storage, maximum_storage; // The pure step for the maximum is a vector of zeros maximum_storage = _mm_setzero_si128(); // The update step for maximum for (int max_y = y - 2; max_y <= y + 2; max_y++) { uint8_t *clamped_row = clamped_storage + (max_y & 7) * clamped_width; for (int max_x = x_base - 2; max_x <= x_base + 2; max_x++) { __m128i v = _mm_loadu_si128( (__m128i const *)(clamped_row + max_x + 2)); maximum_storage = _mm_max_epu8(maximum_storage, v); } } // The pure step for the minimum is a vector of // ones. Create it by comparing something to // itself. minimum_storage = _mm_cmpeq_epi32(_mm_setzero_si128(), _mm_setzero_si128()); // The update step for minimum. for (int min_y = y - 2; min_y <= y + 2; min_y++) { uint8_t *clamped_row = clamped_storage + (min_y & 7) * clamped_width; for (int min_x = x_base - 2; min_x <= x_base + 2; min_x++) { __m128i v = _mm_loadu_si128( (__m128i const *)(clamped_row + min_x + 2)); minimum_storage = _mm_min_epu8(minimum_storage, v); } } // Now compute the spread. __m128i spread = _mm_sub_epi8(maximum_storage, minimum_storage); // Store it. _mm_storeu_si128((__m128i *)(output_row + x_base), spread); } } free(clamped_storage); } return c_result; }This takes about 9.2 milliseconds.

This means that using pure C++ with libraries of this kind, we either have short and slow code or complex, fast code.

Halide as the solution

Bored yet? Halide comes to the rescue. The same high performance can be achieved by this piece of Halide code (again, adapted from halide tutorial 9)

class ValueSpreadGenerator : public Halide::Generator<ValueSpreadGenerator> { public: Input<Buffer<uint8_t>> input{"input", 2}; Output<Buffer<uint8_t>> output{"spread", 2}; void generate() { // DEFINITIONS Var x("x"), y("y"); Func clamped; Expr x_clamped = clamp(x, 0, input.width() - 1); Expr y_clamped = clamp(y, 0, input.height() - 1); clamped(x, y) = input(x_clamped, y_clamped); RDom box(-2, 5, -2, 5); output(x, y) = (maximum(clamped(x + box.x, y + box.y)) - minimum(clamped(x + box.x, y + box.y))); // SCHEDULE Var yo, yi; output.split(y, yo, yi, 32).parallel(yo); output.vectorize(x, 16); clamped.store_at(output, yo).compute_at(output, yi); } };This takes 6.8 milliseconds.

To be fair, this generates a binary with a C-like function, that needs to be wrapped as follows, to get the same cv::Mat function(const cv::Mat& input) signature.

cv::Mat computeSpreadHalideFast(const cv::Mat& input_) { cv::Mat_<uint8_t> output_(input_.size(), input_.type()); Halide::Buffer<uint8_t> input = Halide::Runtime::Buffer<uint8_t>( input_.data, input_.cols, input_.rows); Halide::Buffer<uint8_t> output = Halide::Runtime::Buffer<uint8_t>( output_.data, output_.cols, output_.rows); value_spread_lib(input.raw_buffer(), output.raw_buffer()); return output_; }But this boilerplate is relatively cheap to maintain as we don’t need to read it once it’s written.

This is certainly much, much closer to directly telling you what it’s doing rather than overwhelming you with detail. On the other hand, this looks a bit magical and I wouldn’t blame you for questioning the sanity and generality of the syntax at first glance. After all, any programmer can make a tool for writing only some special cases more declaratively, while being too narrow to be useful in practice. But Halide is good enough to be useful in the image processing domain. The trick is the synergy of various kinds of optimizations that it can do under the hood, and letting you steer it (in the “schedule” section) enough that you can actually get the optimal performance. And the “steering” is a very quick process, which means that you can try various configurations of these optimizations in minutes, not days, as usual in hand-written C++. As for the generality, it’s really quite impressive, but with some caveats described later.

Just to give you a feel of the power, these things are handled by Halide:

- Generating optimal native machine code from those sources, along with all the micro optimizations done by the LLVM core.

- Operations on local neighborhoods require having special code for the edges of the image. These are often separate loops when written by hand. Halide handles this for you, you only declare what to do on the edges.

- Vectorization, parallelization and storage in slices and tiles, as declared in the schedule section.

- Halide automatically does some other optimizations that you would want to have, such as inlining, using circular buffers for storage and grouping computation in optimal ways.

Having your code in Halide form has additional advantages:

- It’s a matter of some quick trial-and-error to tune the performance for a particular processor (Assuming that you really need it. If it’s a similar architecture, it’s probably already fast.), while the result is guaranteed to remain correct because you only change the schedule section.

- Halide has multiple backends, so we can totally run this on a GPU through CUDA or OpenCL. In theory the code remains the same, although some changes are needed to make this optimal, especially in the schedule section.

- Arguably it’s easy to read the algorithmic part, at least when one is used to Halide, and, when needed, to write some equivalent code in any other language.

2. Why is it not so popular then?

It solves a relatively narrow problem. Just how narrow is, in my humble opinion, not easy to determine by an average programmer. Also, there are some key usability problems that, while not invalidating Halide as an implementer’s tool, make it hard to justify using it for other code that you don’t need to optimize with Halide.

Array focus

It is a language for n-dimensional array processing, with grids and parallel processing of local neighborhoods (also called “stencil operations”) as the main focus. This already narrows the usability, because, for example, in image processing we often deal with sparse objects like keypoints, paths and blending regions. What if we have an image of size 800×600 and want to produce corners, not a 800×600 mask of corners, but the actual std::vector of positions, of size, for example, 173? Halide can’t do it.

Harris corners (red) and an array where their positions could be stored. Source: my own work A language where you can’t allocate memory depending on contents, and where you can’t make a simple loop over a vector or a dictionary is not a good fit for those problems. Furthermore, some problems that are often formulated in terms of processing the whole array are really sparse for some inputs. For example, morphological erosion can have lower time complexity (O(sqrt(W*H)) instead of O(W*H)), if all you are eroding is a boundary of a large uniform object. If you have the location of any boundary pixel, you can just trace the whole boundary without even considering all the other pixels.

A useful way to think about this limitation of Halide is to treat it like tensorflow, but with more control over optimization. Imagine implementing a hash table in tensorflow. Even if we could make it, we probably wouldn’t get any advantage over C++. To be clear, Halide is arguably a better fit for a hash table than tensorflow, just not the right solution to the problem anyway.

More technically, there are some fundamental limitations of Halide syntax:

- No iterative programming.

- No recursion. This is actually more complicated. There is no true recursion as we know it, but Halide can do limited recursion over a subset of dimensions, called reduction domains, and the recursion depth must be bounded by arguments given to the Halide program. For example, you can’t take any number N computed during the execution of a Halide program, and do a recursion of depth N.

- No free-form memory allocation. In Halide there are 2 worlds: the world of array sizes and the world of array contents. They don’t mix. If they did, Halide couldn’t infer bounds for arrays and could optimize stencil operations as well. This means, for example, that you can’t allocate an array with the size equal to the number of Harris corners.

You have to write the equations yourself

But, Halide is in theory very good not only for image processing such as denoising, HDR, or tone mapping but even for more computer vision-related tasks, like object detection, that are normally implemented using deep neural networks. Neural network operations, particularly convolutional ones, are the kind of massively parallel tasks that Halide should be good at.

But this more advanced use doesn’t happen. Why is that? On the level of Deep learning framework *user*, this doesn’t happen because the frameworks like pytorch and tensorflow are much more high level than Halide. It is merely an implementation language. Prototyping ML and DL solutions requires going beyond writing your own neural network code and, instead, involves using the provided frameworks for organizing experiments, doing evaluation, using various prebuilt elements such as layer types, activations, loss functions et cetera. They are already available, debugged, optimized and presented for consumption with a python interface. There is even the whole ecosystem of cloud services, such as Amazon SageMaker, to scale and further automate the tasks. Even if you could squeeze some extra cycles by implementing your networks with Halide, it would prove to be a laborious task that only the richest corporations can afford. The speed advantage needs to be really life-changing for anyone to reach for the unconventional solution. If you wanted to, though, there is some autodiffentiation in Halide.

But this point goes beyond deep learning and autodiff. What we would want is to reach for existing code, which there is little of, because the use of Halide simply hasn’t scaled to that level yet.

Unfitness for prototyping for quality

The thing is, that the slow programs that generate intermediate images are very easy to write in python or C++, compared to their Halide equivalents. This means that prototyping for quality, meaning the development stage that happens before you know exactly what you want to compute, should be done in python or C++, using OpenCV or a similar image processing library. For example, you might want to try different kinds of denoising algorithms for a given camera, to choose the one that gives the best resulting image. This has to be distinguished from prototyping for speed, where the output image remains unchanged and you are trying to determine what kind of processing speeds are possible and what they depend on. For this kind, Halide is helpful.

The following are some reasons for this unfitness:

- You have to write the equations yourself.

- Halide is focused on grids and non-recursive algorithms, which means that injecting some other paradigm code in the middle of the Halide program requires calling outside Halide. At this point if one wants to make the code readable, one would normally write the whole intermediate result to memory, defeating the purpose of Halide.

- There is a significant cost of writing glue code between an existing C++ code (that you usually have when prototyping, usually in the form of external libraries) and Halide.

- Prototyping the best quality and speed at the same time is not easy with Halide, in general, because:

- Adding something to the Halide code sometimes results in errors from schedule, which means that you have to rewrite it in those cases, in order to change something.

- Performance (memory or speed) of Halide code sometimes scales unintuitively when you add something. This is largely because Halide does optimizations under the hood and it can be surprising when they appear or disappear. This means that when you write too long a Halide program, there will normally be something about its performance that you won’t expect. This can be somewhat alleviated by adding some „compute_root” calls, but they slow down the program and even they don’t entirely remove doubts about some aspects.

- There is no easy way to truly abstract away pieces of code for reuse. Yes, there are Halide functions, but these have much more limited applicability than C++ functions. They are more like functions from math rather than in programming. They apply to the meaning part, or in other words, the algorithm only, and their relation with the schedule section is more complicated. If you try to write a program that calls function A and then gives the result to function B, you will learn that their schedules connect and don’t work as expected. This is because by default the functions share input domains and redefining them is hard. And there is no abstraction of returning an array value that sits in memory and is then given to another call. Something that is trivial in C++ doesn’t exist in Halide.

The last point is particularly problematic because it makes it hard to write libraries in halide, for use in other Halide programs. This paints a picture of Halide as a language for prototyping optimization only, rather than a convenience language, like python, that may be used for prototyping things to create some proof of concept or a demo.

The blackboxiness

Halide, while declarative, doesn’t let you control everything. That’s its point but it also makes some things harder to do.

Readability

Halide generates the loops for you, in the form of compiled machine code. You don’t normally see them.

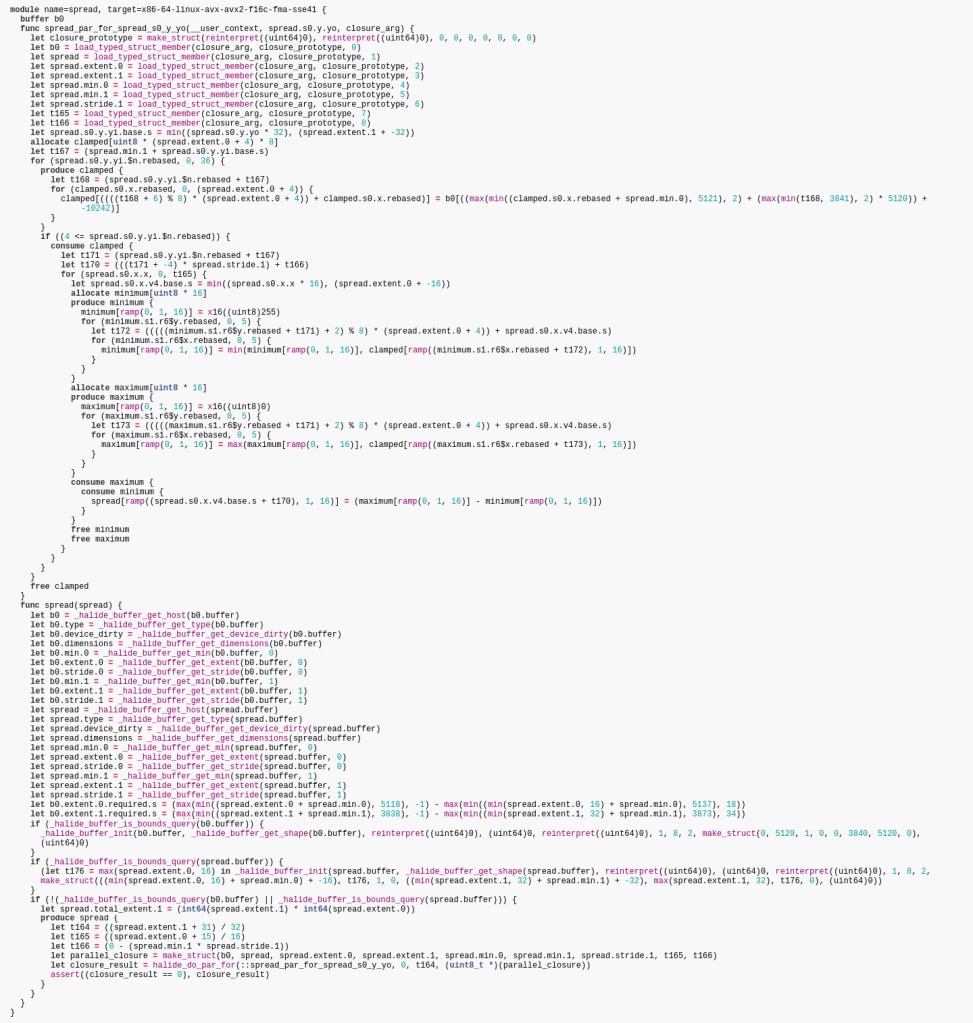

But Halide can spit out pseudocode for what’s run. Let’s examine this. First of all, this isn’t a readable pseudocode, for the same reason the equivalent hand-optimized C++ code is not readable. It can’t be. I mean you can read the individual lines, but you won’t be able to tell why they are there. And even if it was as readable as possible, unless you are Halide implementer, you can’t be 100% sure of what each piece of the pseudocode actually means. These things have the disadvantage that the training and documentation has to be 100% perfect (which they aren’t), or you can’t make sure you haven’t misread something, because you can’t just take that pseudocode, tweak something and run it to see what happens.

Besides, the format is a bit elaborate. Take, for example, the short example we’ve seen, with the 5×5 spreads. This is its pseudocode:

Quick look reveals that there are a lot of assertions. If we cut those off, we can zoom in a little bit.

Ideally, if you could read it, you would want to look at something like this once in a while to see what is really happening under the hood. But it simply takes too much time to pour through such code, especially with no prospect of being sure that what you’ve understood is true and when you change the schedule every 5 minutes. Besides, you haven’t written this code. What if you’ve missed something that you were supposed to spot, like an unexpected 100 MB allocation?

Besides, not knowing that you can dump pseudocode can be an issue too, with organizations made of people with various levels of skill and engagement.

None of these problems exist with a manually written C++ code, where something must be written by hand before it even executes.

To give an example of a readability problem, in this code for computing Harris corners (this is a shortened version of harris_generator.cpp in Halide repository), can you tell what is likely to be the peak memory during execution?

Expr sum3x3(Func f, Var x, Var y) { return f(x - 1, y - 1) + f(x - 1, y) + f(x - 1, y + 1) + f(x, y - 1) + f(x, y) + f(x, y + 1) + f(x + 1, y - 1) + f(x + 1, y) + f(x + 1, y + 1); } class Harris : public Halide::Generator<Harris> { public: Input<Buffer<float, 3>> input{"input"}; Output<Buffer<float, 2>> output{"output"}; void generate() { Var x("x"), y("y"), c("c"); // Algorithm Func gray("gray"); gray(x, y) = (0.299f * input(x, y, 0) + 0.587f * input(x, y, 1) + 0.114f * input(x, y, 2)); Func Iy("Iy"); Iy(x, y) = gray(x - 1, y - 1) * (-1.0f / 12) + gray(x - 1, y + 1) * (1.0f / 12) + gray(x, y - 1) * (-2.0f / 12) + gray(x, y + 1) * (2.0f / 12) + gray(x + 1, y - 1) * (-1.0f / 12) + gray(x + 1, y + 1) * (1.0f / 12); Func Ix("Ix"); Ix(x, y) = gray(x - 1, y - 1) * (-1.0f / 12) + gray(x + 1, y - 1) * (1.0f / 12) + gray(x - 1, y) * (-2.0f / 12) + gray(x + 1, y) * (2.0f / 12) + gray(x - 1, y + 1) * (-1.0f / 12) + gray(x + 1, y + 1) * (1.0f / 12); Func Ixx("Ixx"); Ixx(x, y) = Ix(x, y) * Ix(x, y); Func Iyy("Iyy"); Iyy(x, y) = Iy(x, y) * Iy(x, y); Func Ixy("Ixy"); Ixy(x, y) = Ix(x, y) * Iy(x, y); Func Sxx("Sxx"); Sxx(x, y) = sum3x3(Ixx, x, y); Func Syy("Syy"); Syy(x, y) = sum3x3(Iyy, x, y); Func Sxy("Sxy"); Sxy(x, y) = sum3x3(Ixy, x, y); Func det("det"); det(x, y) = Sxx(x, y) * Syy(x, y) - Sxy(x, y) * Sxy(x, y); Func trace("trace"); trace(x, y) = Sxx(x, y) + Syy(x, y); output(x, y) = det(x, y) - 0.04f * trace(x, y) * trace(x, y); Var xi("xi"), yi("yi"); // schedule // 0.92ms on an Intel i9-9960X using 16 threads const int vec = natural_vector_size<float>(); output.split(y, y, yi, 32) .parallel(y) .vectorize(x, vec); gray.store_at(output, y) .compute_at(output, yi) .vectorize(x, vec); Ix.store_at(output, y) .compute_at(output, yi) .vectorize(x, vec); Iy.store_at(output, y) .compute_at(output, yi) .vectorize(x, vec); Ix.compute_with(Iy, x); } };This is harder to tell in Halide because it doesn’t show memory allocations as explicitly as the C++ code does.

In general, it’s a bit hard to tell how the performance, parallelization and especially the memory consumption will change if you change the code. In pure C++, it can be easier because you get loop indentation, explicit parallelization and explicit allocations which make those things easy to spot. I wish there was a more explicit version of Halide where I can add pieces of pseudocode as documentation and have the compiler error if they don’t tell the truth.

Process overhead

Now that we’ve established that we don’t know exactly what is happening, there is another problem. Our colleagues who don’t know Halide don’t even know how to read the code. Both issues have an easy but unfortunate and laborious solution: write some equivalent, unoptimized C++ code and unit tests that make sure that it gives the same results as the Halide version. This also helps with the prototyping problem, because you can switch the tests off temporarily, tweak the C++ version until you like the new quality, and then Hopefully you will be able to write the Halide version that matches C++ result and have better performance.

As a result we are left with three times as much code, compared to what we expected when we started learning Halide.

But there is more code to add. For example, can you tell what schedules were tried in the course of optimizing code and are known to be slower? Only a well-written comment can solve this problem. Even version control software doesn’t solve it because it’s illogical to put slower schedules in extra commits, it wouldn’t be apparent to the reader that the extra commits exist, and they would be quickly buried in history. Of course, this issue of documenting past experiments also exists in manually written C++. It’s just that the comparison with C++ looks much better if this aspect of the process is ignored. Halide makes it seem that you can try different schedules so quickly that it no longer matters whether you really understand what’s happening or know about what was tried before. But Halide is not that good.

As always in programming, a lot of code quality is the result of the good process and talent, rather than the choice of tools. And an extra tool often causes more code to appear, just due to increasing the number of tools by 1.

Multitude of open source algorithms are already available

Halide’s scope is limited simply by what is already available. See, for example, the OpenCV Imgproc module, which contains a lot of algorithms, most of which could take advantage of Halide. If this is already available, and you don’t need to merge those with something else, why roll your own implementation? To be clear, this point is not a criticism of Halide, just a statement of what you would use first, given the need.

Optimization incompleteness

This is not some computability theory consideration, but a much more down-to-earth problem. In particular, it’s not easy to know

- how far have you really gone with the optimization.

- how far *can* you go with the optimization

Halide solves the „optimize quickly” problem but it doesn’t solve the „finish optimizing” problem, or even the „I know where I’m at” problem.

Let’s focus on the second one first.

Halide obscures what has been done by forcing the declarative syntax on us.

I can imagine that if someone is either:

- Halide author

- A top-tier image processing expert with decades of experience in optimizing the code.

then one can expect that a given Halide code will have certain performance with a reasonable degree of accuracy (still not perfectly though – part of the experience is knowing that you have to make measurements to really know anything).

But what if you aren’t one of those people? How do you know that you haven’t made a bug in the schedule, so that your code doesn’t run how you think it does, and is 2 times slower than it should? Sadly, you can’t know that for sure. You just have to stare at your code, or keep modifying the schedule until you discover those kinds of bugs by accident.

Then, how do you know how far you can go? Can you assign a number to it, like 2 ms before writing the implementation? You may wonder what this question has to do with Halide. The same problem exists with pure C++ or any other language. The thing is, by obscuring what has been done, you are much less sure of what yet remains to be done. Are you fully using the L1 cache? Don’t know? Then how do you know that a given optimization that improves the L1 cache usage is a worthy pursuit?

Does it mean that you are better off writing pure C++ code and then tiling, parallelizing and vectorizing by hand? Probably not, for the same reason that you are normally better off using python for prototyping ML projects instead of, say, C++. You simply can try 10x more things in the same period of time, so you are going to get there faster anyway even though you aren’t sure where you are at this point. In the end, it comes down to what kind of requirements you have. If you have something specific like „go below 1s”, then Halide is ok, because you can easily measure that. But if you have to „be better than competition”, with no clear idea what they do, then you may sometimes find it hard to justify to your management that you’ve done everything that you could, even if your result would be much worse with pure C++.

Both of these problems can be worked around by considering the max theoretical throughput of devices as well as by comparing with supposedly optimized implementations of similar algorithms. But Halide doesn’t give an advantage here, you still need some expert knowledge to do this.

Build system troubles

There are 2 use cases that I will distinguish for the purpose of build system discussion:

- The first one I call the realistic use case because it’s aligned with the typical use of the host language – C++. In particular, in this use case, there is an assumption that the code is already compiled and will execute as fast as possible the first time it’s called. This is especially critical for latency-sensitive and resource-constrained applications, but also has implications for unit testing, and in other unexpected situations.

- The unrealistic use case is when you can use JIT mode (compile during execution and then reuse compiled code). This is only useful if the application is throughput-sensitive, but not latency-sensitive. It’s also useful in some toy programs, if you don’t care about speed but just want to test Halide syntax. But it’s too slow to allow a similar programming model to, say, Java, where JIT happens fast, under the hood, to optimize some critical sections. To make the severity of the problem more apparent, the JIT version of the spread sample, described in the first half of this article, takes 970 ms, compared to 7 ms of the optimized version. The extra time is spent compiling the code.

The realistic use case

The build system needs to be more complicated, because Halide adds another phase. This works well with modern CMake, but it’s understandable that it may cause estra worries, especially if you are doing strange things for unrelated reasons and/or have to support other tools that require certain options set or conventions followed.

It’s also a bit hard to discover and get into the best way to build stuff with Halide, especially when you cross compile. The 2 phases are:

- You build binaries that will generate the code that you need. This is when the code in Halide is built.

- You generate the code that you need and link it with your project.

This allows everything to be built upfront which is the default in C++ projects and usually required or assumed in any performance sensitive application.

To make things harder on the user, Halide disguises its power by formulating initial tutorials in terms of the JIT mode (not useful in the realistic use case), where the compilation of Halide code happens at the runtime of the final program. This creates an illusion that a researcher can get into Halide easier because of less setup of the code, but I doubt that it happens much anyway, because Halide is not productive in the first place, as compared to python or other research languages. Halide is really only attractive for those performance sensitive cases.

Now here comes the hard to understand fact about building with Halide. Let’s say you have an Android project. This means that you have your compiler and build system on, for example, a Linux system, and you cross compile for the Android platform and usually for an ARM processor. How does Halide come into play with this? It works beautifully, but you have to discover and understand that some of your code (the Halide generator part) needs to be built for *Linux*, then run on *Linux* to generate *Android* libraries that you can then link to your *Android* code. The best way to handle the generator part is to use the CMake subproject. This means making a separate folder with CMakeLists.txt file for the generator part only, and calling ExternalProject_Add to add its configuration and building as a step in your main project. If you don’t do this and

- Have everything in one project instead, some of your Android build options may creep in to Linux build, or,

- Have 2 separate projects instead, one for the generator part, and using a shell script to build them in sequence, you aren’t doing the smartest thing, and you may lose incremental builds.

Phew! Don’t even get me started on choosing between the 32-bit and the 64-bit Halide release when cross compiling.

The unrealistic use case

This is when you only use the JIT mode. I can imagine that it seems attractive when you only care about throughput. After all, Halide even lets you precompile stuff before the first call, using the compile_jit method. Feel free to use JIT, but, while avoiding extra CMake code, it means that the Halide sources will compile every time you run your program, whether for testing or in production. Imagine a large unit test suite that compiles a ton of little Halide snippets, 1s each, in addition to actually testing the code. It can become very impractical very quickly. And besides, the fact that you can JIT some code doesn’t mean that you won’t want to use some precompiled Halide. And at this point, the build system advantages of Halide JIT disappear.

3. Summary

Although the title of the article is somewhat clickbaity, I want to emphasize that Halide is an excellent tool for optimizing image processing code. It lets me shorten some optimization tasks, saving weeks at a time. Issues remain though, and, by writing this, I wanted to create a resource for people to navigate this complicated topic, and figure out how they can use Halide within their organization. Let me know if this article helped.

4. Resources

The source code for this article can be found at https://github.com/klosworks/halide_articles. You can also use this code as a starting point for your Halide projects.

5. References and disclaimers

Scientific References

Hasinoff, S. W., Sharlet, D., Geiss, R., Adams, A., Barron, J. T., Kainz, F., Chen, J., & Levoy, M. (2016). Burst photography for high dynamic range and low-light imaging on mobile cameras. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 35(6), 1-12.

Ragan-Kelley, J., Barnes, C., Adams, A., Paris, S., Durand, F., & Amarasinghe, S. (2013). Halide: a language and compiler for optimizing parallelism, locality, and recomputation in image processing pipelines. ACM SIGPLAN Notices, 48(6), 519-530. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2499370.2462176

Shacham, O., & Reynders, M. (2017, October 17). Pixel Visual Core: image processing and machine learning on Pixel 2. The Keyword | Google. Retrieved July 5, 2022, from https://www.blog.google/products/pixel/pixel-visual-core-image-processing-and-machine-learning-pixel-2/

Disclaimers

This article builds on some open source code from the Halide repository. It is under this composite license. I believe that the fragments used in this article fall under the MIT part, quoted here:

Copyright (c) 2012-2020 MIT CSAIL, Google, Facebook, Adobe, NVIDIA CORPORATION, and other contributors.

Developed by:

The Halide team

http://halide-lang.orgPermission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of

this software and associated documentation files (the „Software”), to deal in

the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to

use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies

of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do

so, subject to the following conditions:The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all

copies or substantial portions of the Software.THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED „AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE. -

The first post

This is my first post on this blog. I’m going to blog about things that interest me in computer vision, image processing, C++ and similar topics. I hope you enjoy my writing and take something useful from it.

-

Subskrybuj

Zapisan/y/a

Masz już konto na WordPress.com? Zaloguj się teraz.